Van Gogh Exhibit Gives Me Fever

This article was first published on 24 August, 2023.

Despite my purist tendencies and general distaste for pop-culture commercialism, last week I bought two tickets to the Van Gogh Immersive Experience at Pleasant Valley Promenade in Raleigh. The day out was a birthday present for a longtime friend who’d suggested it; and, as we drove around the vast strip mall - which seemed to be as much asphalt as it was storefronts - I determined to keep an open mind and prepared to be pleasantly surprised.

We parked near a large, windowless building at the very back of the mall and walked toward the giant image of Van Gogh’s Starry Night covering the front wall, as seen in selfies posted by countless Facebook friends.

The inside was similar to a popular exhibit in an Art Museum, except that there were no windows - anywhere. I asked the woman at the front desk how it felt to work all day in a place with no natural light. I’d no doubt it would depress me. (In after thought and given Van Gogh’s obsession with Nature, I’m sure it would depress him as well.)

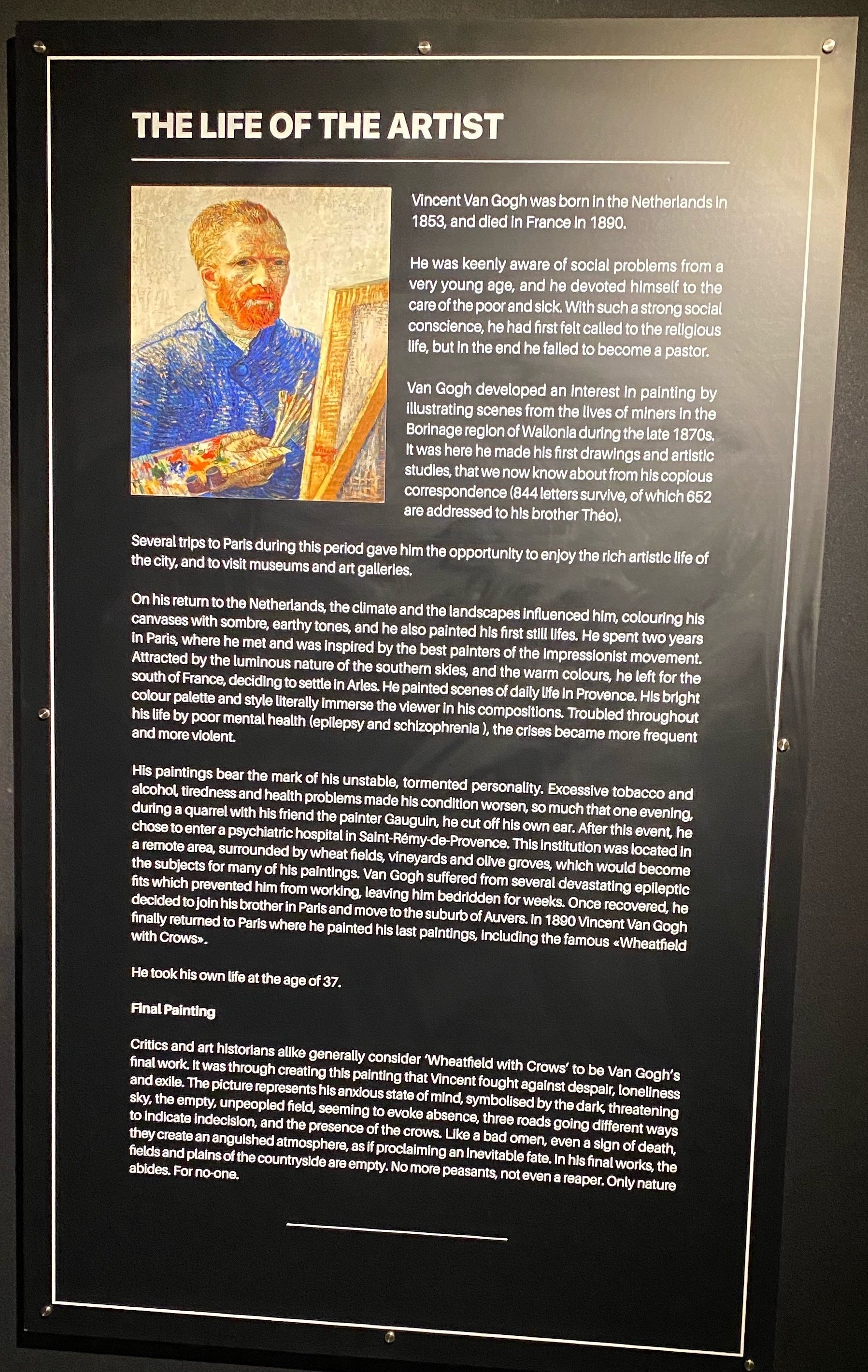

As we entered the exhibit, images of Van Gogh’s paintings were projected on the walls alongside accounts of Van Gogh’s life and art. I'd forgotten how much I felt for this man when I first discovered him in college. The specifics of his life, much of which I’d also forgotten, fascinated me now as they did then, which should come as no surprise given his multigenerational fame and popularity.

Most adults can tell you that Van Gogh was the mad artist who cut off his own his ear. Many are also familiar with his famous sunflower paintings and the swirling depths of Starry Night, the work for which he is most known. But comparatively few understand the beautifully tragic depths of Vincent van Gogh’s life.

The things I (re-) learned:

I had forgotten that Van Gogh lived with the famous artist Paul Gauguin for the couple months before the former’s alleged behavioral swings crescendoed to the ear-cutting episode and eventually his apparent suicide. Van Gogh’s ear mutilation in reaction to yet another heated argument with Gauguin is historically portrayed as a horrific symptom of the debilitating “manic depression” (bipolar disorder) that defines Van Gogh’s legacy. But what of his toxic relationship with the far more successful, influential, and narcissistic Gauguin - the only person Van Gogh ever called “master”?

Gauguin had turned his back on his wife of eleven years and their five children, as well as several illegitimate children and their mothers - at least two of which were teenagers. Ashley Remer, a New Zealand-based American curator, describes Gauguin as “an arrogant, overrated, patronising pedophile” and insists that, if they were photographs, his paintings would be “way more scandalous” and “we wouldn’t have been accepting of the images”.

Van Gogh was a preacher before he was a painter. Despite the way he alienated people with his nervous, over-excited and often quarrelsome nature, Van Gogh was a kind and generous person who believed in human value and social justice. Combined with his manic depression, Van Gogh’s troubled soul was vulnerable to a narcissist like Gauguin, who unsympathetically invalidated Vincent’s feelings and concerns. It didn’t help that Van Gogh revered Gauguin. It was only because of Van Gogh’s unrelenting invitations (and Gauguin’s financial needs) that Gauguin finally agreed to live with him.

I identify with Van Gogh’s addictions (in his case, Art and absinthe) and his increasingly violent overreactions to Gauguin’s repeated and belittling dismissals. I’ve experienced this myself, though with far less intensity. I can’t imagine how much worse things could be if I were clinically bipolar (or worse), as Van Gogh was, and had no modern medication to ease my storms. This is why Van Gogh’s work speaks to so many. We have all experienced anxiety, overreactions, and toxic relationships to varying degrees; and many of us have contemplated doing the worst in response. But Van Gogh actually did it. Which must make him crazy, right?

The things that made Van Gogh:

People are fascinated by the concept of insanity, perhaps because most of us are one step away from it. They enjoy Van Gogh’s paintings as physical manifestations of the madness that trails us all. Crazy sells.

Funny thing is, both Van Gogh’s ear self-mutilation and suicide may not even be true. Some historians insist that Gauguin, who was an accomplished fencer, sliced off Van Gogh’s ear with the sword he regularly carried late at night for defense. It appears just as likely that Van Gogh was shot not by himself, but by a “gang of teenage hooligans who enjoyed getting drunk and bullying the tortured artist”. Despite their holes, the ear self-mutilation and suicide rumors gained momentum throughout the 20th century and have made Van Gogh the quitessential “artist maudit: a troubled, unpredictable, erratic genius.”

If the public thought that Van Gogh merely lost his ear at the hands of an inebriated artist friend and was ultimately shot like a dog in the street by a bunch of drunken teenagers, would his paintings be as popular and valuable as they are today?

I like to think they would. Because perhaps the most valuable and courageous aspect of Van Gogh’s story is how, after his ear-mutilation and despite the historically terrible reputation of mental asylums, he sought help by voluntarily admitting himself into the Saint-Paul-de-Mausole psychiatric hospital in Saint-Rémy. Though it wasn’t a public insane asylum, it was a terrifying environment that Van Gogh may not have survived without his obsessively creative spirit (no family or nearby friends visited). He made 150 paintings during his time there and was released on 16 May 1890, at his own request. I call that a success, even if not a cure.

Whether or not the bullet that killed him two months later was self-inflicted, Van Gogh laid in bed for 36 hours and even smoked his pipe while he waited for death. Dr. Gachet, who had little experience with gunshot wounds, and Vincent’s brother Theo both described him, in the hours before his death, as stoic and accepting - a man ready for the peace that death would bring. Given his strong Christian faith and its aversion to suicide, perhaps Van Gogh was grateful someone else had ended his innate suffering in this world, so that he didn’t have to.

The “Immersive” Experience:

Although the Van Gogh Immersive exhibit predictably goes with the traditional Self-Mutilation and Suicide story, it goes into more detail regarding the artist’s life than most exhibits I’ve seen, which prompted me to dig deeper when I got home. In the end, I was grateful for the opportunity to reflect on Van Gogh’s Art, which may just as likely have prevented his self-ejection from this world as caused him to go mad and kill himself.

Though I’d much rather have seen the actual paintings, it was a delight to take undivided time to read about Van Gogh while seeing so many of his pieces projected before me. The life-sized, 3-D compilation of his paintings of the psychiatric asylum, his bedroom in Arles, and the Japanese Courtesan were entertaining if not authentic.

And the giant bust and slide show of Van Gogh’s self portraits and floral paintings, respectively, were mesmerizing, despite being highly two-dimensional and a lot like watching a giant screensaver. The “immersive” experience itself occurred in a large rectangular room, giant projections of Van Gogh paintings and the designs and structures therein covering the walls. Though entertaining and somewhat meditative, this, too, was more like a glorified slide show with special effects, the images drifting into one another in digitally-defined ways that the creators tried to make seem random and artistic. My favorite part was the giant chronological progression of Van Gogh’s self portraits, which occurred only once and could only be seen again if I sat through the whole show a second time.

After 1.5 hours, we were too spent to spend the additional $5/person for the “one-of-a-kind virtual reality experience” offered at the end of the exhibit. Turns out this is the only way you actually get to walk through what the creators call “Van Gogh’s universe.” As I watched people (mostly kids) in their virtual-reality helmets, I figured it won’t be long before we can do this in the comfort of our own homes; and, with my susceptibility to motion sickness these days, it probably would have nauseated me anyway.

When we entered the gift shop at the end, the real meaning behind this Immersive Experience was obvious: monetary profit. Backpacks, jewelry, tea sets, yoga mats, coffee mugs, playing cards, cell-phone and attache cases, rubics cubes, flip flops - just about anything that can portray images from Van Gogh’s paintings was available for purchase; and every item bore the “Immersive Experience” brand. For twenty dollars or so, you could get a photo of yourself, Disney-like, in front of a giant image of Starry night. They even had a set of lapel pins comprised of 2 pieces: Van Gogh’s head and an ear. Everything seemed to emulate the popular and commercial trivialization of Van Gogh’s life and Art , which didn’t stop me from buying a reverse-folding umbrella featuring a print of Van Gogh’s Almond Blossoms on the underside. (Hey, I’ve needed a new umbrella for over a year now.)

Customer Service:

Fever, the only organization handling ticket sales (at least in America), has tickets for children as young as 4 years old and family passes at reduced prices; so it’s no coincidence that I saw more than a few young children at the exhibit. I wondered how well they could read; and, if so, whether they did read any of the tragic background material that accompanied the pretty pictures. During the light show finale, I watched and heard several grow restless before leaving the room with their parents. I wondered about the conversations they’d have on the way home - whether their parents would overlook the depths of Van Gogh’s tragic story, as I would if I were discussing his work with a five-year-old: “He was a very, very sad man who made beautiful paintings.” Later, while watching the news and contemplating the current mental health crisis in this country, I wondered if any of those kids had troublesome thoughts, as Van Gogh and most of his artist contemporaries did, and if this exhibit prompted them to talk to their parents about it. I felt certain the possibility would make Van Gogh happy.

As for the business side of the exhibit: To obtain my tickets, which cost me $35 a piece plus $10 in additional fees, Fever required me to upload an app that takes up sizable cell-phone memory, can track who knows what, and flashes marketing material at me whenever I open it. It really pisses me off when companies make me upload their app to utilize my purchase, particularly when they could more easily have emailed me a pdf of each ticket. It didn’t surprise me when I could find no phone number on the Raleigh Van Gogh and Fever websites. For an exhibition “that has been touring since 2017 with +5,000,000 visitors,” these guys are making money hand over fist on a skeleton budget. They don’t have a single real painting. You’d think they could at least fix the typos on their information boards.

Conclusion:

The Van Gogh Immersive Experience in Raleigh is worth it if you can get a coupon code to cut the price in half. $40/ticket is an exorbitant price when all the information in the exhibit can be found in a book or on the Internet, and you don’t even get to see any of Van Gogh’s real paintings. Often, I wondered whether the colors I was seeing were Van Gogh’s or the Immersive Experience’s creators’. In addition, the exhibit makes dogmatic statements - like Van Gogh was color blind, had epilepsy, and only sold one painting - that remain conjecture among art historians.

Here’s a great biographical documentary I found on Youtube: https://youtu.be/P8rTfLkS2l8.

More relevant links:

https://vangoghexpo.com/raleigh/

https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2010/01/04/van-goghs-ear

https://www.theartnewspaper.com/2019/12/06/ten-myths-about-vincent-van-gogh

https://news.artnet.com/art-world/was-van-gogh-killed-new-research-says-he-was-shot-159637

https://www.biography.com/news/vincent-van-gogh-final-years-days

https://audioboom.com/posts/7923949-van-gogh-immersive-experience

https://www.cnn.com/style/article/vincent-van-gogh-pistol-auction-france-intl-scli/index.html